Edo Fires Part 1: Hanabi

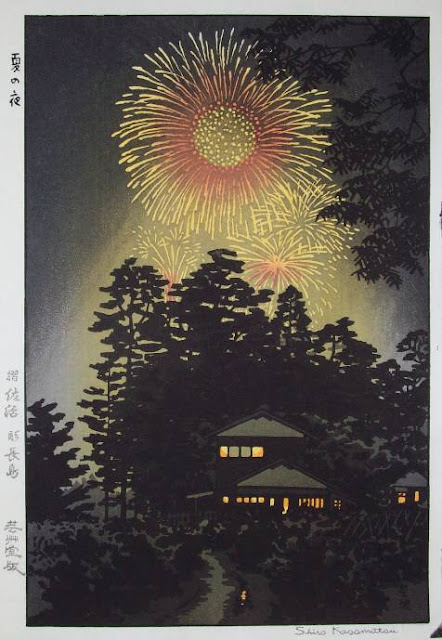

Let’s start with

the joyful fires, since it is firework season in Japan.

Whilst there are

mentions of gunpowder being introduced to Japan through China at least from the

15th century, it was not widely used until matchlock-configured arquebuses

(tanegashima) made their way to Japan through the Portuguese in the mid-16

century.

Fireworks (花火 hanabi

– fire flowers) were seemingly imported later on as the first official mention

of them being observed (by Tokugawa Ieyasu no less) was in 1613. They came

through an English merchant on the first English voyage to Japan named

John Saris who was accompanied by a Chinese merchant whose name I unfortunately

couldn’t find.

During the Edo period, the need for gunpowder was virtually non-existent so pyrotechnicians could put their effort into developing fire flowers (such as chrysanthemum or peonies which we still see today). Sohke Hanabi Kagiya was founded in 1659 and the 15th generation chief still operates their shop in Tokyo’s Edogawa ward. Taking the dangers of fireworks as fire hazards seriously, their good reputation allowed them to become official purveyor to the Shogunate. Around 1700, fireworks were confined to the surroundings or the Sumida river in the east side of Edo and Daimyō and merchants would have Kagiya display fireworks above the river as they enjoyed the summer evenings on pleasure boats.

In 1733, to

commemorate the over one million lives lost to famines, epidemics and overty

the year prior, Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshimune held a firework festival on the banks

of the Sumida river in Edo which is still happening every year.

Here is a great article by the Mainichi Shinbun on Kagiya and how fireworks are made: https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20210813/p2a/00m/0na/031000c

More on symbolism and history: Liu-Brennan, Damien, and Mio Bryce. 2010. "Japanese Fireworks (Hanabi): The Ephemeral Nature and Symbolism." The International Journal of the Arts in Society: Annual Review 4 (5). Open Access (here)

Comments

Post a Comment